Preprint of a review by Iosif Lazaridis, The evolutionary history of human populations in Europe.

Interesting excerpts:

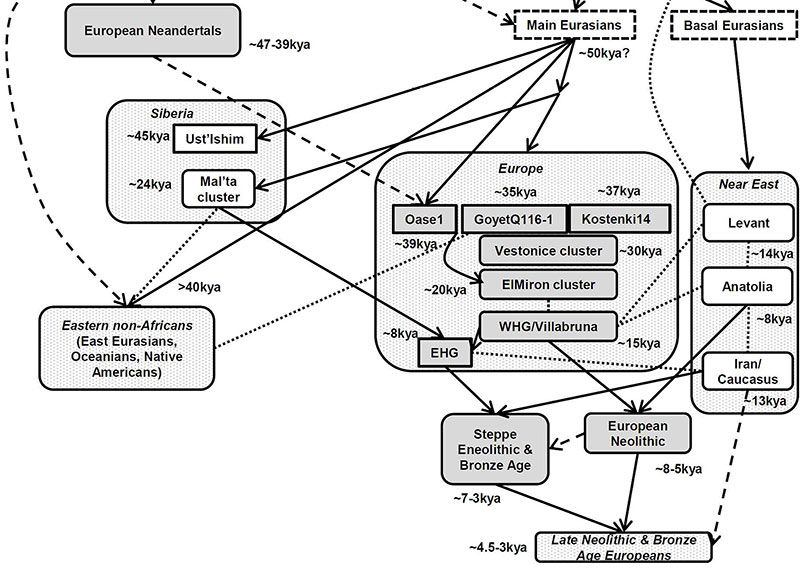

Steppe populations during the Eneolithic to Bronze Age were a mix of at least two elements[28], the EHG who lived in eastern Europe ~8kya and a southern population element related to present-day Armenians[28], and ancient Caucasus hunter-gatherers[22], and farmers from Iran[24]. Steppe migrants made a massive impact in Central and Northern Europe post- 5kya[28,43]. Some of them expanded eastward, founding the Afanasievo culture[43] and also eventually reached India[24]. These expansions are probable vectors for the spread of Late Proto-Indo-European[44] languages from eastern Europe into both mainland Europe and parts of Asia, but the lack of steppe ancestry in the few known samples from Bronze Age Anatolia[45] raises the possibility that the steppe was not the ultimate origin of Proto-Indo-European (PIE), the common ancestral language of Anatolian speakers, Tocharians, and Late Proto-Indo Europeans. In the next few years this lingering mystery will be solved: either Anatolian speakers will be shown to possess steppe-related ancestry absent in earlier Anatolians (largely proving the steppe PIE hypothesis), or they will not (largely falsifying it, and pointing to a Near Eastern PIE homeland).

Our understanding of the spread of steppe ancestry into mainland Europe is becoming increasingly crisp. Samples from the Bell Beaker complex[46] are heterogeneous, with those from Iberia lacking steppe ancestry that was omnipresent in those from Central Europe, casting new light on the “pots vs. people” debate in archaeology, which argues that it is dangerous to propose a tight link between material culture and genetic origins. Nonetheless, it is also dangerous to dismiss it completely. Recent studies have shown that people associated with the Corded Ware culture in the Baltics[23,33] were genetically similar to those from Central Europe and to steppe pastoralists[28,43], and the people associated with the Bell Beaker culture in Britain traced ~90% of their ancestry to the continent, being highly similar to Bell Beaker populations there. Bell Beaker-associated individuals were bearers of steppe ancestry into the British Isles that was also present in Bronze Age Ireland[47], and Iron Age and Anglo-Saxon England[48]. The high genetic similarity between people from the British Isles and those of the continent makes it more difficult to trace migrations into the Isles. This high similarity masks a very detailed fine-scale population structure that has been revealed by study of present-day individuals[49]; a similar type of analysis applied to ancient DNA has the potential to reveal fine-grained population structure in ancient European populations as well.

Steppe ancestry did arrive into Iberia during the Bronze Age[50], but to a much lesser degree. A limited effect of steppe ancestry in Iberia is also shown by the study of mtDNA[51], which shows no detectible change during the Chalcolithic/Early Bronze Age[51], in contrast to central Europe[52]. Sex-biased gene flow has been implicated in the spread of steppe ancestry into Europe[33,53], although the presence and extent of such bias has been debated[54,55]. One aspect of the demographies of males and females was clearly different, as paternally-inherited Y-chromosome lineages experienced a bottleneck <10 kya which is not evident in maternally-inherited mtDNA[56], suggesting that many men living today trace their patrilineal ancestry to a relatively small number of men of the Neolithic and Bronze Ages.

Firstly, Tocharian (mentioned side by side with Anatolian and LPIE) has been discussed by linguists for quite some time now to be a more archaizing language than the rest, hence the linguistic proposal that it separated first – found to correspond beautifully with the expansion of Khvalynsk/Repin into Afanasevo – ; but it separated first from the common Late PIE trunk. Anatolian clearly separated earlier, from a Middle PIE stage.

Secondly, while Genomics could no doubt falsify the Balkan route for Anatolian, and make us come back to a Maykop route from the steppe (or even a Near Eastern PIE homeland, who knows), I doubt such falsification could come simply from sampled “Anatolian speakers”:

If there is no steppe ancestry in Anatolian speakers (of the 2nd millennium BC), a dismissal of the mainstream migration model could happen only when both potential routes of expansion, the selected cultures from the Balkans and the Caucasus, are sampled in the appropriate time period since the estimated separation (i.e. from the 5th millennium BC), until one of both routes shows the right migration picture.

On the other hand, if some samples from either Romania/Bulgaria or the Caucasus (and/or Anatolian speakers) show steppe ancestry and/or R1b-M269 lineages, as is expected, then the matter won’t need much more explanation.

In fact, the text goes on to define how male lineages experienced a bottleneck after ca. 8000 BC, i.e. accompanying Neolithisation – probably including the formation of Sredni Stog and early Khvalynsk, as it is becoming now clear – , when explaining how it is possible to demonstrate that East Bell Beaker migrants (of R1b-L23 lineages, it is to be understood) with few steppe ancestry reached Iberia.

This was already pointed out not long ago by David Reich, and I am glad to see more scholars showing the importance of taking phylogeography into account over statistical methods when assessing migrations, even if it is only used in those cases in which it does not disrupt too much previous interpretations, like that of the 2015 papers and the proposal of the ‘Yamnaya ancestral component’.

I found it refreshing that for the first time Corded Ware migrants – or, rather, their shared genetic relationship with Eneolithic steppe groups – were accepted (if only indirectly) as a confounding factor in assessing migrations of Bell Beakers. It is a step in the right direction, and it is a relief to read this from someone working with the Reich Lab.

Not just a few (and not only amateurs) are still scratching their heads trying to explain with the most imaginative (and unnecessary) novel migration routes the elevated steppe ancestry and closer relation (PCA cluster, FST, F3, etc.) to CWC and Yamna (due evidently to the absorbed CWC population) in some of the recently published Bell Beaker samples from Central Europe, the Netherlands, and later in Great Britain, compared to samples of South-East Europe near the Middle to Upper Danube region, the obvious homeland of East Bell Beakers, formed from Yamna settlers.

I found it also interesting that Lazaridis mentioned a southern population element related to CHG and Iran farmers. This should help dissipate the hype that some have artificially created as of late over a potential Northern Iranian homeland based on a single paragraph from David Reich’s book.

EDIT (9 MAY 2018). Lazaridis posted an answer to my questioning of potential Proto-Anatolian origins divided in tweets (I post a link to the first tweet, then the text in full):

A review of my review:https://t.co/k0Q3H6STsH

with some thoughts to follow on origin of Anatolian languages/speakers 1/

— Iosif Lazaridis (@iosif_lazaridis) May 7, 2018

The steppe hypothesis predicts some genetic input from eastern Europe (EHG) to Anatolia.

– Bronze Age Anatolians (Lazaridis et al. 2017) from historically IE-speaking Pisidia lack EHG; more samples obviously needed

Possibilities:

- Additional Anatolian samples will have EHG: consistent with steppe PIE

- Additional Anatolian samples will not have EHG, then either:

- Steppe not PIE homeland

- Steppe PIE homeland but linguistic impact in Anatolia vastly greater than genetic impact

Tentative steppe->Anatolia movements reach Balkans early (Mathieson et al. 2018) and Armenia (some EHG in Lazaridis et al. 2016).

But not the last leg to Anatolia_ChL (Lazaridis et al. 2016) or Anatolia_BA (Lazaridis et al. 2017).

- If Anatolians consistently don’t have EHG, steppe PIE is very difficult to affirm; Near Eastern alternative likely (contributing CHG/Iran_N-related ancestry to both western Anatolia/steppe)

- If Anatolians have EHG, one could further investigate by what route they got it.

One way or another PIE homeland problem is almost solved IMHO, which is what my review tries to get at in that short section

Related:

- Haplogroup R1b-L51 in Khvalynsk samples from the Samara region dated ca. 4250-4000 BC

- David Reich on social inequality and Yamna expansion with few Y-DNA subclades

- Domestication spread probably via the North Pontic steppe to Khvalynsk… but not horse riding

- North Pontic steppe Eneolithic cultures, and an alternative Indo-Slavonic model

- The Lower Danube during the Eneolithic, and the potential Proto-Anatolian community

- Consequences of O&M 2018 (III): The Balto-Slavic conundrum in Linguistics, Archaeology, and Genetics

- Consequences of O&M 2018 (I): The latest West Yamna “outlier”

- Olalde et al. and Mathieson et al. (Nature 2018): R1b-L23 dominates Bell Beaker and Yamna, R1a-M417 resurges in East-Central Europe during the Bronze Age

- The Indo-European demic diffusion model, and the “R1b – Indo-European” association

- Proto-Indo-European homeland south of the Caucasus?

- On the potential origin of Caucasus hunter-gatherer ancestry in Eneolithic steppe cultures

- Consequences of O&M 2018 (II): The unsolved nature of Suvorovo-Novodanilovka chiefs, and the route of Proto-Anatolian expansion

- New Ukraine Eneolithic sample from late Sredni Stog, near homeland of the Corded Ware culture