Open access A finely resolved phylogeny of Y chromosome Hg J illuminates the processes of Phoenician and Greek colonizations in the Mediterranean, by Finocchio et al. Scientific Reports (2018) Nº 7465.

Abstract (emphasis mine):

In order to improve the phylogeography of the male-specific genetic traces of Greek and Phoenician colonizations on the Northern coasts of the Mediterranean, we performed a geographically structured sampling of seven subclades of haplogroup J in Turkey, Greece and Italy. We resequenced 4.4 Mb of Y-chromosome in 58 subjects, obtaining 1079 high quality variants. We did not find a preferential coalescence of Turkish samples to ancestral nodes, contradicting the simplistic idea of a dispersal and radiation of Hg J as a whole from the Middle East. Upon calibration with an ancient Hg J chromosome, we confirmed that signs of Holocenic Hg J radiations are subtle and date mainly to the Bronze Age. We pinpointed seven variants which could potentially unveil star clusters of sequences, indicative of local expansions. By directly genotyping these variants in Hg J carriers and complementing with published resequenced chromosomes (893 subjects), we provide strong temporal and distributional evidence for markers of the Greek settlement of Magna Graecia (J2a-L397) and Phoenician migrations (rs760148062). Our work generated a minimal but robust list of evolutionarily stable markers to elucidate the demographic dynamics and spatial domains of male-mediated movements across and around the Mediterranean, in the last 6,000 years.

Interesting excerpts:

Two features of our tree are at odds with the simplistic idea of a dispersal of Hg J as a whole from the Middle East towards Greece and Italy and an accompanying radiation26. First, there is little evidence of sudden diversification between 15 and 5 kya, a period of likely population increase and pressure for range expansion, due to the Agricultural revolution in the Fertile Crescent. Second, within each subclade, lineages currently sampled in Turkey do not show up as preferentially ancestral. Both findings are replicated and reinforced by examining the previous landmark studies. Our Turkish samples do not coalesce preferentially to ancestral nodes when mapped onto these studies’ trees.

Additional relevant information on the entire Hg J comes from the discontinuous distribution of J2b-M12. The northern fringe of our sample is enriched in the J2b-M241 subclade, which reappears in the gulf of Bengal38,45, with low frequencies in the intervening Iraq46 and Iran47. No J2b-M12 carriers were found among 35 modern Lebanese, as contrasted to one of two ancient specimens from the same region35.

In summary, a first conclusion of our sequencing effort and merge with available data is that the phylogeography of Hg J is complex and hardly explained by the presence of a single population harbouring the major lineages at the onset of agriculture and spreading westward. A unifying explanation for all the above inconsistencies could be a centre of initial radiation outside the area here sampled more densely, i.e. the Caucasus and regions North of it, from which different Hg J subclades may have later reached mainland Italy, Greece and Turkey, possibly following different routes and times. Evidence in this direction comes from the distribution of J2a-M41045,48 and the early-49 or mid-Holocene50 southward spread of J1.

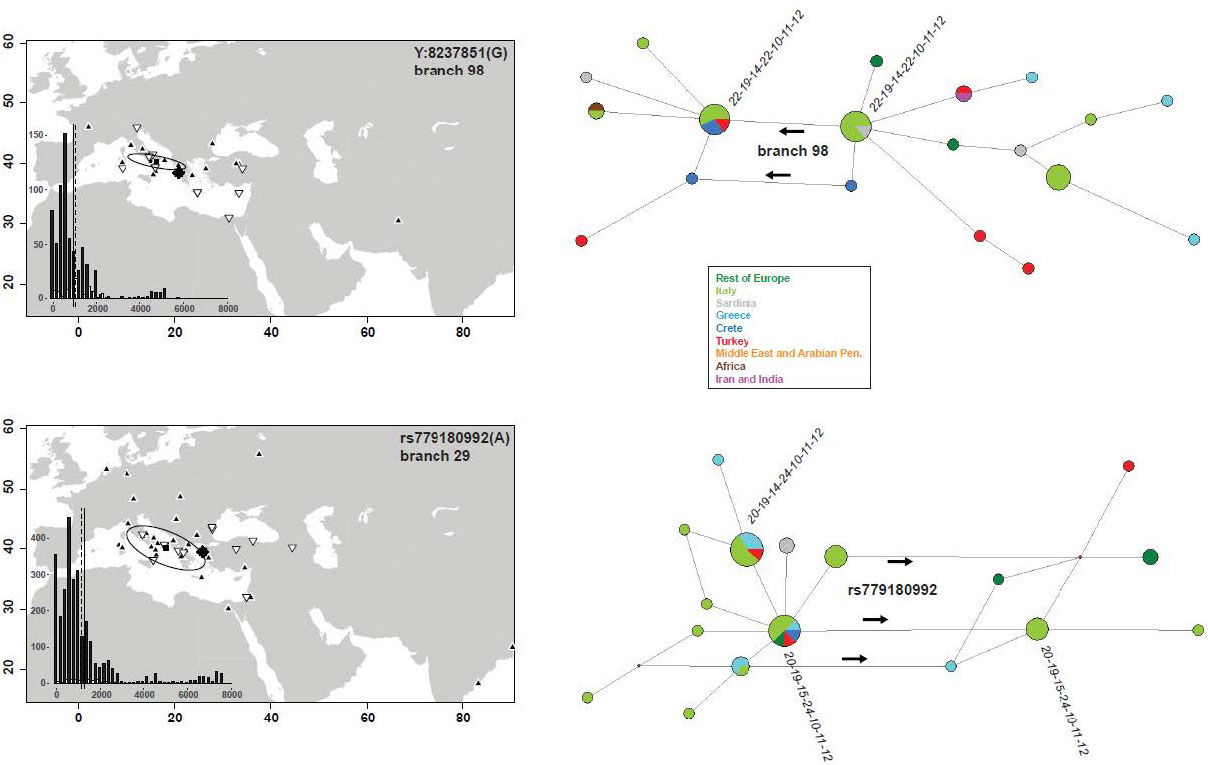

The lineage defined by rs779180992, belonging to J2b-M205, and dated at 4–4.5 kya, has a radically different distribution, with derived alleles in Continental Italy, Greece and Northern Turkey, and two instances in a Palestinian and a Jew. The interpretation of the spread of this lineage is not straightforward. Tentative hypotheses are linked to Southward movements that occurred in the Balkan Peninsula from the Bronze Age29,53, through the Roman occupation and later54.

The slightly older (5.6–6.3 kya) branch 98 lineage displays a similar trend of a Eastward positioning of derived alleles, with the notable difference of being present in Sardinia, Crete, Cyprus and Northern Egypt. This feature and the low frequency of the parental J2a-M92 lineage in the Balkans27 calls for an explanation different from the above.

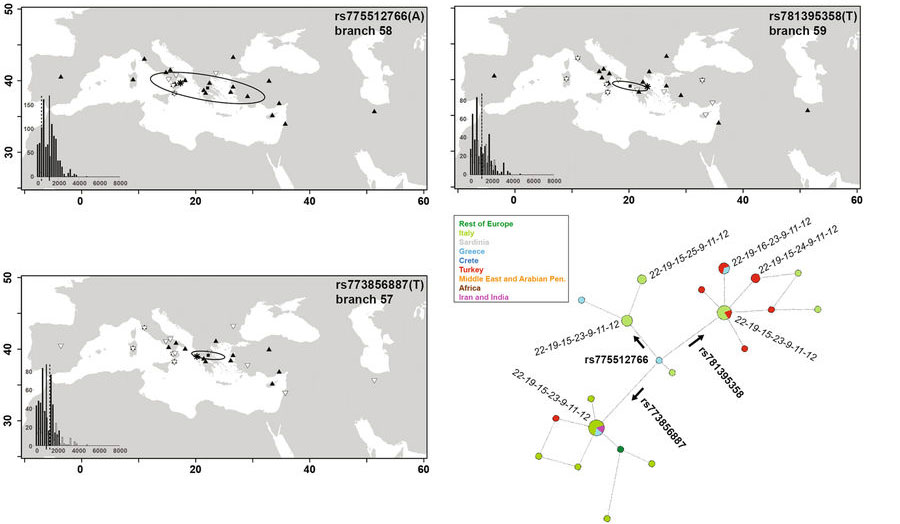

Finally, we explored the distribution of J2a-L397 and three derived lineages within it. J2a-L397 is tightly associated with a typical DYS445 6-repeat allele. This has been hypothesized as a marker of the Greek colonizations in the Mediterranean55, based on its presence in Greek Anatolia and Provence (France), a region with attested Iron Age Greek contribution. All of our chromosomes in this clade were characterized also by DYS391(9), confirming their Anatolian Greek signature. We resolved the J2a-L397 clade to an unprecedented precision, with three internal markers which allow a finer discrimination than STRs. The ages of the three lineages (2.0–3.0 kya) are compatible with the beginning of the Greek colonial period, in the 8th century BCE. The three subclades have different distributions (Fig. 2B), with two (branches 57, 59) found both East and West to Greece, and one only in Italy (branch 58). As to Mediterranean Islands, J2a-L397 was found in Cyprus56 and Crete43. Its presence as one of the three branches 57–59 will represent an important test. In Italy all three variants were found mainly along the Western coast (18/25), which hosted the preferred Greek trade cities. The finding of all three differentiated lineages in Locri excludes a local founder effect of a single genealogy. Interestingly, an important Greek colony was established in this location, with continuity of human settlement until modern times. The sample composed of the same subjects displayed genetic affinities with Eastern Greece and the Aegean also at autosomal markers57. In summary, the distributions of branches 57–59 mirror the variety of the cities of origin and geographic ranges during the phases of the colonization process58.

So, there you have it, another proof that haplogroup J and CHG-related ancestry in the Mediterranean was mainly driven by different (and late) expansions of historic peoples.

Related:

- Consequences of Damgaard et al. 2018 (I): EHG ancestry in Maykop samples, and the potential Anatolian expansion routes

- Genetic origins of Minoans and Mycenaeans and their continuity into modern Greeks

- No large-scale steppe migration into Anatolia; early Yamna migrations and MLBA brought LPIE dialects in Asia

- Lazaridis’ evolutionary history of human populations in Europe

- Haplogroup R1b-L51 in Khvalynsk samples from the Samara region dated ca. 4250-4000 BC

- Domestication spread probably via the North Pontic steppe to Khvalynsk… but not horse riding

- The Lower Danube during the Eneolithic, and the potential Proto-Anatolian community

- Consequences of O&M 2018 (II): The unsolved nature of Suvorovo-Novodanilovka chiefs, and the route of Proto-Anatolian expansion

- On the potential origin of Caucasus hunter-gatherer ancestry in Eneolithic steppe cultures

- The Indo-European demic diffusion model, and the “R1b – Indo-European” association

- Proto-Indo-European homeland south of the Caucasus?