Scythian samples from the North Pontic area are far more complex than what could be seen at first glance. From the new Y-SNP calls we have now thanks to the publications at Molgen (see the spreadsheet) and in Anthrogenica threads, I think this is the basis to work with:

NOTE. I understand that writing a paper requires a lot of work, and probably statistical methods are the main interest of authors, editors, and reviewers. But it is difficult to comprehend how any user of open source tools can instantly offer a more complex assessment of the samples’ Y-SNP calls than professionals working on these samples for months. I think that, by now, it should be clear to everyone that Y-DNA is often as important (sometimes even more) than statistical tools to infer certain population movements, since admixture can change within few generations of male-biased migrations, whereas haplogroups can’t…

Srubna

Srubna-Andronovo samples are as homogeneous as they always were, dominated by R1a-Z645 subclades and CWC-related (steppe_MLBA) ancestry.

The appearance of one (possibly two) R-Z280 lineages in this mixed Srubna-Alakul region of the southern Urals and this early (1880-1690 BC, hence rather Pokrovka-Alakul) points to the admixture of R1a-Z93 and R1a-Z280 already in Abashevo, which also explains the wide distribution of both subclades in the forest zones of Central Asia.

If Abashevo is the cornerstone of the Indo-Iranian / Uralic community, as it seems, the genetic admixture would initially be quite similar, undergoing in the steppes a reduction to haplogroup R1a-Z93 (obviously not complete), at the same time as it expanded to the west with Pokrovka and Srubna, and to the east with Petrovka and Andronovo. To the north, similar reductions will probably be seen following the Seima-Turbino phenomenon.

NOTE. Another R1a-Z280 has been found in the recent sample from Bronze Age Poland (see spreadsheet). As it appears right now in ancient and modern DNA, there seems to be a different distribution between subclades:

- R1a-Z280 (formed ca. 2900 BC, TMRCA ca. 2600 BC) appears mainly distributed today to the east, in the forest and steppe regions, with the most ‘successful’ expansions possibly related to the spread of Abashevo- and Battle Axe-related cultures (Indo-Iranian and Uralic alike).

- R1a-M458 (formed ca. 2700, TMRCA ca. 2700 BC) appears mainly distributed to the north, from central Europe to the east – but not in the steppe in aDNA, with the most ‘successful’ expansions to the west.

M458 lineages seem thus to have expanded in the steppe in sizeable numbers only after the Iranian expansions (see a map of modern R1a distributions) i.e. possibly with the expansion of Slavs, which supports the model whereby cultures from central-east Europe (like Trzciniec and Lusatian), accompanied mainly by M458 lineages, were responsible for the expansion of Proto-Balto-Slavic (and later Proto-Slavic).

The finding of haplogroup R1a-Z93, among them one Z2123, is no surprise at this point after other similar Srubna samples. As I said, the early Srubna expansion is most likely responsible for the Szólád Bronze Age sample (ca. 2100-1700 BC), and for the Balkans BA sample (ca. 1750-1625 BC) from Merichleri, due to incursions along the central-east European steppe.

Cimmerians

Cimmerian samples from the west show signs of continuity with R1a-Z93 lineages. Nevertheless, the sample of haplogroup Q1a-Y558, together with the ‘Pre-Scythian’ sample of haplogroup N (of the Mezőcsát Culture) in Hungary ca. 980-830 BC, as well as their PCA, seem to depict an origin of these Pre-Scythian peoples in populations related to the eastern Central Asian steppes, too.

NOTE. I will write more on different movements (unrelated to Uralic expansions) from Central and East Asia to the west accompanied by Siberian ancestry and haplogroup N with the post of Ugric-Samoyedic expansions.

Scythians

The Scythian of Z2123 lineage ca. 375-203 BC from the Volga (in Mathieson et al. 2015), together with the sample scy193 from Glinoe (probably also R1a-Z2123), without a date, as well as their common Steppe_MLBA cluster, suggest that Scythians, too, were at first probably quite homogeneous as is common among pastoralist nomads, and came thus from the Central Asian steppes.

The reduction in haplogroup variability among East Iranian peoples seems supported by the three new Late Sarmatian samples of haplogroup R1a-Z2124.

Approximate location of Glinoe and Glinoe Sad (with Starosilya to the south, in Ukrainian territory):

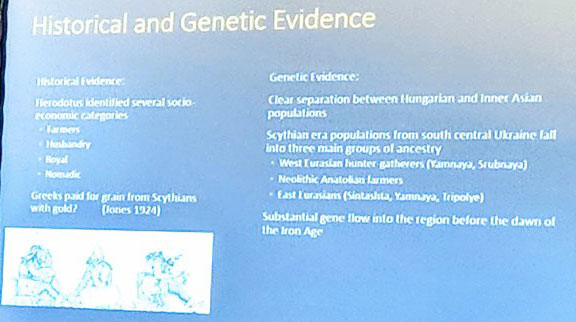

This initial expansion of Scythians does not mean that one can dismiss the western samples as non-Scythians, though, because ‘Scythian’ is a cultural attribution, based on materials. Confirming the diversity among western Scythians, a session at the recent ISBA 8:

Genetic continuity in the western Eurasian Steppe broken not due to Scythian dominance, but rather at the transition to the Chernyakhov culture (Ostrogoths), by Järve et al.

The long-held archaeological view sees the Early Iron Age nomadic Scythians expanding west from their Altai region homeland across the Eurasian Steppe until they reached the Ponto-Caspian region north of the Black and Caspian Seas by around 2,900 BP. However, the migration theory has not found support from ancient DNA evidence, and it is still unclear how much of the Scythian dominance in the Eurasian Steppe was due to movements of people and how much reflected cultural diffusion and elite dominance. We present new whole-genome results of 31 ancient Western and Eastern Scythians as well as samples pre- and postdating them that allow us to set the Scythians in a temporal context by comparing the Western Scythians to samples before and after within the Ponto-Caspian region. We detect no significant contribution of the Scythians to the Early Iron Age Ponto-Caspian gene pool, inferring instead a genetic continuity in the western Eurasian Steppe that persisted from at least 4,800–4,400 cal BP to 2,700–2,100 cal BP (based on our radiocarbon dated samples), i.e. from the Yamnaya through the Scythian period.

(…) Our results (…) support the hypothesis that the Scythian dominance was cultural rather than achieved through population replacement.

Detail of the slide with admixture of Scythian groups in Ukraine:

The findings of those 31 samples seem to support what Krzewińska et al. (2018) found in a tiny region of Moldavia-south-western Ukraine (Glinoi, Glinoi Sad, and Starosilya).

The question, then, is as follows: if Scythian dominance was “cultural rather than achieved through population replacement”…Where are the R1b-Z2103 from? One possibility, as I said in the previous post, is that they represent pockets of Iranian R1b lineages in the steppes descended from eastern Yamna, given that this haplogroup appears in modern populations from a wide region surrounding the steppes.

The other possibility, which is what some have proposed since the publication of the paper, is that they are related to Thracians, and thus to Palaeo-Balkan populations. About the previously published Thracian individuals in Sikora et al. (2014):

For the Thracian individuals from Bulgaria, no clear pattern emerges. While P192-1 still shows the highest proportion of Sardinian ancestry, K8 more resembles the HG individuals, with a high fraction of Russian ancestry.

Despite their different geographic origins, both the Swedish farmer gok4 and the Thracian P192-1 closely resemble the Iceman in their relationship with Sardinians, making it unlikely that all three individuals were recent migrants from Sardinia. Furthermore, P192-1 is an Iron Age individual from well after the arrival of the first farmers in Southeastern Europe (more than 2,000 years after the Iceman and gok4), perhaps indicating genetic continuity with the early farmers in this region. The only non-HG individual not following this pattern is K8 from Bulgaria. Interestingly, this individual was excavated from an aristocratic inhumation burial containing rich grave goods, indicating a high social standing, as opposed to the other individual, who was found in a pit.

The following are excerpts from A Companion to Ancient Thrace (2015), by Valeva, Nankov, and Graninger (emphasis mine):

Thracian settlements from the 6th c. BC on:

(…) urban centers were established in northeastern Thrace, whose development was linked to the growth of road and communication networks along with related economic and distributive functions. The early establishment of markets/emporia along the Danube took place toward the middle of the first millennium BCE (Irimia 2006, 250–253; Stoyanov in press). The abundant data for intensive trade discovered at the Getic village in Satu Nou on the right bank of the Danube provides another example of an emporion that developed along the main artery of communication toward the interior of Thrace (Conovici 2000, 75–76).

Undoubtedly the most prominent manifestation of centralization processes and stratification in the settlement system of Thrace arrives with the emergence of political capitals – the leading urban centers of various Thracian political formations.

Their relationships with Scythians and Greeks

The Scythian presence south of the Danube must be balanced with a Thracian presence north of the river. We have observed Getae there in Alexander’s day, settled and raising grain. For Strabo the coastlands from the Danube delta north as far as the river and Greek city of Tyras were the Desert of the Getae (7.3.14), notable for its poverty and tracklessness beyond the great river. He seems to suggest also that it was here that Lysimachus was taken alive by Dromichaetes, king of the Getae, whose famous homily on poverty and imperialism only makes sense on the steppe beyond the river (7.3.8; cf. Diod. 21.12; further on Getic possessions above the Danube, Paus. 1.9 with Delev 2000, 393, who seems rather too skeptical; on poverty, cf. Ballesteros Pastor 2003). This was the kind of discourse more familiarly found among Scythians, proud and blunt in the strength of their poverty. However, as Herodotus makes clear, simple pastoralism was not the whole story as one advanced round into Scythia. For he observes the agriculture practiced north and west of Olbia. These were the lands of the Alizones and the people he calls the Scythian Ploughmen, not least to distinguish them from the Royal Scythians east of Olbia, in whose outlook, he says, these agriculturalist Scythians were their inferiors, their slaves (Hdt. 4.20). The key point here is that, as we began to see with the Getan grain-fields of Alexander’s day, there was scope for Thracian agriculturalists to maintain their lifestyles if they moved north of the Danube, the steppe notwithstanding. It is true that it is movement in the other direction that tends to catch the eye, but there are indications in the literary tradition and, especially, in the archaeological record that there was also significant movement northward from Thrace across the Danube and the Desert of the Getae beyond it.

Greek literary sources were not much concerned with Thracian migration into Scythia, but we should observe the occasional indications of that process in very different texts and contexts. At the level of myth, it is to be remembered that Amazons were regularly considered to be of Thracian ethnicity from Archaic times onward and so are often depicted in Thracian dress in Greek art (Bothmer 1957; cf. Sparkes 1997): while they are most familiar on the south coast of the Black Sea, east of Sinope, they were also located on the north coast, especially east of the Don (the ancient Tanais). Herodotus reports an origin-story of the Sauromatians there, according to which this people had been created by the union of some Scythian warriors with Amazons captured on the south coast and then washed up on the coast of Scythia (4.110). While the story is unhistorical, it is not without importance. First, it reminds us that passage north from the Danube was not the only way that Thracians, Thracian influence, and Thracian culture might find their way into Scythia. There were many more and less circuitous routes, especially by sea, that could bring Thrace into Scythia. Secondly, the myth offered some ideological basis for the Sauromatian settlement in Thrace that Strabo records, for Sauromatians might claim a Thracian origin through their Amazon forebears. Finally, rather as we saw that Heracles could bring together some of the peoples of the region, we should also observe that Ares, whose earthly home was located in Thrace by a strong Greek and Roman tradition, seems also to have been a deity of special significance and special cult among the Scythians. So much was appropriate, especially from a Classical perspective, in associations between these two peoples, whose fame resided especially in their capacity for war.

This broad picture of cultural contact, interaction, and osmosis, beyond simple conflict, provides the context for a range of archaeological discoveries, which – if examined separately – may seem to offer no more than a scatter of peculiarities. Here we must acknowledge especially the pioneering work of Melyukova, who has done most to develop thinking on Thracian–Scythian interaction. As she pointed out, we have a good example of Thracian–Scythian osmosis as early as the mid-seventh century bce at Tsarev Brod in northeastern Bulgaria, where a warrior’s burial combines elements of Scythian and Thracian culture (Melyukova 1965). For, while the manner of his burial and many of the grave goods find parallels in Scythia and not Thrace, there are also goods which would be odd in a Scythian burial and more at home in a Thracian one of this period (notably a Hallstatt vessel, an iron knife, and a gold diadem). Also interesting in this regard are several stone figures found in the Dobrudja which resemble very closely figures of this kind (baby) known from Scythia (Melyukova 1965, 37–38). They range in date from perhaps the sixth to the third centuries bce, and presumably were used there – as in Scythia – to mark the burials of leading Scythians deposited in the area. Is this cultural osmosis? We should probably expect osmosis to occur in tandem with the movement of artefacts, so that only good contexts can really answer such questions from case to case. However, the broad pattern is indicated by a range of factors. Particularly notable in this regard is the observable development of a Thraco-Scythian form of what is more familiar as “Scythian animal style,” a term which – it must be understood – already embraces a range of types as we examine the different examples of the style across the great expanse from Siberia to the western Ukraine. As Melyukova observes, Thrace shows both items made in this style among Scythians and, more numerous and more interesting, a Thracian tendency to adapt that style to local tastes, with observable regional distinctions within Thrace itself. Among the Getae and Odrysians the adaptation seems to have been at its height from the later fifth century to the mid-third century (Melyukova 1965, 38; 1979).

The absence of local animal style in Bulgaria before the fifth century bce confirms that we have cultural influences and osmosis at work here, though that is not to say that Scythian tradition somehow dominated its Thracian counterpart, as has been claimed (pace Melyukova 1965, 39; contrast Kitov 1980 and 1984). Of particular interest here is the horse-gear (forehead-covers, cheek-pieces, bridle fittings, and so on) which is found extensively in Romania and Bulgaria as well as in Scythia, both in hoarded deposits and in burials. This exemplifies the development of a regional animal style, not least in silver and bronze, which problematizes the whole issue of the place(s) of its production. Accordingly, the regular designation as “Thracian” of horse-gear from the rich fourth century Scythian burial of Oguz in the Ukraine becomes at least awkward and questionable (further, Fialko 1995). And let us be clear that this is no minor matter, nor even part of a broader debate about the shared development of toreutics among Thracians and Scythians (e.g., Kitov 1980 and 1984). A finely equipped horse of fine quality was a strong statement and striking display of wealth and the power it implied

(…) while Thracian pottery appears at Olbia, Scythian pottery among Thracians is largely confined to the eastern limits of what should probably be regarded as Getic territory, namely the area close to the west of the Dniester, from the sixth century bce. Rather exceptional then is the Scythian pottery noted at Istros, which has been explained as a consequence of the Scythian pursuit of the withdrawing army of Darius and, possibly, a continued Scythian grip on the southern Danube in its aftermath (Melyukova 1965, 34). The archaeology seems to show us, therefore, that the elite Thracians and Scythians were more open to adaptation and acculturation than were their lesser brethren.

Conclusion

(…) we see distinct peoples and organizations, for example as Sitalces’ forces line up against the Scythians. Much more striking, however, against that general background, are the various ways in which the two peoples and their elites are seen to interact, connect, and share a cultural interface. We see also in Scyles’ story how the Greek cities on the coast of Thrace and Scythia played a significant role in the workings of relationships between the two peoples. It is not simply that these cities straddled the Danube, but also that they could collaborate – witness the honors for Autocles, ca. 300 bce (SEG 49.1051; Ochotnikov 2006) – and were implicated with the interactions of the much greater non-Greek powers around them. At the same time, we have seen the limited reality of familiar distinctions between settled Thracians and nomadic Scythians and the limited role of the Danube too in dividing Thrace and Scythia. The interactions of the two were not simply matters of dynastic politics and the occasional shared taste for artefacts like horse-gear, but were more profoundly rooted in the economic matrix across the region, so that “Scythian” nomadism might flourish in the Dobrudja and “Thracian-style” agriculture and settlement can be traced from Thrace across the Danube as far as Olbia. All of that offers scant justification for the Greek tendency to run together Thracians and Scythians as much the same phenomenon, not least as irrational, ferocious, and rather vulgar barbarians (e.g., Plato, Rep. 435b), because such notions were the result of ignorance and chauvinism. However, Herodotus did not share those faults to any degree, so that we may take his ready movement from Scythians to Thracians to be an indication of the importance of interaction between the two peoples whom he had encountered not only as slaves in the Aegean world, but as powerful forces in their own lands (e.g., Hdt. 4.74, where Thracian usage is suddenly brought into his account of Scythian hemp). Similarly, Thucydides, who quite without need breaks off his disquisition on the Odrysians to remark upon political disunity among the Scythians (Thuc. 2.97, a favorite theme: cf. Hdt. 4.81; Xen., Cyr. 1.1.4). As we have seen throughout this discussion, there were many reasons why Thracians might turn the thoughts of serious writers to Scythians and vice versa.

It seems, following Sikora et al. (2014), that Thracian ‘common’ populations would have more Anatolian Neolithic ancestry compared to more ‘steppe-like’ samples. But there were important differences even between the two nearby samples published from Bulgaria, which may account for the close interaction between Scythians and Thracians we see in Krzewińska et al. (2018), potentially reflected in the differences between the Central, Southern and the South-Central clusters (possibly related to different periods rather than peoples??).

If these R1b-Z2103 were descended from Thracian elites, this would be the first proof of Palaeo-Balkan populations showing mainly R1b-Z2103, as I expect. Their appearance together with haplogroup I2a2a1b1 (also found in Ukraine Neolithic and in the Yamna outlier from Bulgaria) seem to support this regional continuity, and thus a long-lasting cultural and ethnic border roughly around the Danube, similar to the one found in the northern Caucasus.

However, since these samples are some 2,500 years younger than the Yamna expansion to the south, and they are archaeologically Scythians, it is impossible to say. In any case, it would seem that the main expansion of R1a-Z645 lineages to the south of the Danube – and therefore those found among modern Greeks – was mediated by the Slavic expansions centuries later.

On the Northern cluster there is a sample of haplogroup R1b-P312 which, given its position on the PCA (apparently even more ‘modern Celtic’-like than the Hallstatt_Bylany sample from Damgaard et al. 2018), it seems that it could be the product of the previous eastward Hallstatt expansion…although potentially also from a recent one?:

Especially important in the archaeology of this interior is the large settlement at Nemirov in the wooded steppe of the western Ukraine, where there has been considerable excavation. This settlement’s origins evidently owe nothing significant to Greek influence, though the early east Greek pottery there (from ca. 650 bce onward: Vakhtina 2007) and what seems to be a Greek graffito hint at its connections with the Greeks of the coast, especially at Olbia, which lay at the estuary of the River Bug on whose middle course the site was located (Braund 2008). The main interest of the site for the present discussion, however, is its demonstrable participation in the broader Hallstatt culture to its west and south (especially Smirnova 2001). Once we consider Nemirov and the forest steppe in connection with Olbia and the other locations across the forest steppe and coastal zone, together with the less obvious movements across the steppe itself, we have a large picture of multiple connectivities in which Thrace bulks large.

While the above description of clear-cut R1a-Steppe and R1b-Balkans is attractive (and probably more reliable than admixture found in scattered samples of unclear dates), the true ancient genetic picture is more complicated than that:

- There is nothing in the material culture of the published western Scythians to distinguish the supposed Thracian elites.

- We have the sample I0575, an Early Sarmatian from the southern Urals (one of the few available) of haplogroup R1b-Z2106, which supports the presence of R1b-Z2103 lineages among Eastern Iranian-speaking peoples.

- We also have DA30, a Sarmatian of I2b lineage from the central steppes in Kazakhstan (ca. 47 BC – 24 AD).

- Other Sarmatian samples of haplogroup R remain undefined.

- There is R1a-Z93 in a late Sarmatian-Hun sample, which complicates the picture of late pastoralist nomads further.

Therefore, the possibility of hidden pockets of Iranian peoples of R1b-Z2103 (maybe also R1b-P312) lineages remains the best explanation, and should not be discarded simply because of the prevalent haplogroups among modern populations, or because of the different clusters found, or else we risk an obvious circular reasoning: “this sample is not (autosomically or in prevalent haplogroups) like those we already had from the steppe, ergo it is not from this or that steppe culture.” Hopefully, the upcoming paper by Järve et al. will help develop a clearer genetic transect of Iranian populations from the steppes.

All in all, the diversity among western Scythians represents probably one of the earliest difficult cases of acculturation to be studied with ancient DNA (obviously not the only one), since Scythians combine unclear archaeological data with limited and conflicting proto-historical accounts (also difficult to contrast with the wide confidence intervals of radiocarbon dates) with different evolving clusters and haplogroups – especially in border regions with strong and continued interactions of cultures and peoples.

With emerging complex cases like these during the Iron Age, I am happy to see that at least earlier expansions show clearer Y-DNA bottlenecks, or else genetics would only add more data to argue about potential cultural diffusion events, instead of solving questions about proto-language expansions once and for all…

"What's happening?" pic.twitter.com/SMFmEuOdMI

— Carlos Quiles (@cquilesc) October 7, 2018

Related

- Early Iranian steppe nomadic pastoralists also show Y-DNA bottlenecks and R1b-L23

- Corded Ware—Uralic (II): Finno-Permic and the expansion of N-L392/Siberian ancestry

- Corded Ware—Uralic (I): Differences and similarities with Yamna

- Haplogroup R1a and CWC ancestry predominate in Fennic, Ugric, and Samoyedic groups

- The Iron Age expansion of Southern Siberian groups and ancestry with Scythians

- Evolution of Steppe, Neolithic, and Siberian ancestry in Eurasia (ISBA 8, 19th Sep)

- Mitogenomes from Avar nomadic elite show Inner Asian origin

- On the origin and spread of haplogroup R1a-Z645 from eastern Europe

- Oldest N1c1a1a-L392 samples and Siberian ancestry in Bronze Age Fennoscandia

- Consequences of Damgaard et al. 2018 (III): Proto-Finno-Ugric & Proto-Indo-Iranian in the North Caspian region

- Genetic prehistory of the Baltic Sea region and Y-DNA: Corded Ware and R1a-Z645, Bronze Age and N1c

- More evidence on the recent arrival of haplogroup N and gradual replacement of R1a lineages in North-Eastern Europe