Open access Tracking Five Millennia of Horse Management with Extensive Ancient Genome Time Series, by Fages et al. Cell (2019).

Interesting excerpts (emphasis mine):

The earliest archaeological evidence of horse milking, harnessing, and corralling is found in the ∼5,500-year-old Botai culture of Central Asian steppes (Gaunitz et al., 2018, Outram et al., 2009; see Kosintsev and Kuznetsov, 2013 for discussion). Botai-like horses are, however, not the direct ancestors of modern domesticates but of Przewalski’s horses (Gaunitz et al., 2018). The genetic origin of modern domesticates thus remains contentious, with suggested candidates in the Pontic-Caspian steppes (Anthony, 2007), Anatolia (Arbuckle, 2012, Benecke, 2006), and Iberia (Uerpmann, 1990, Warmuth et al., 2011). Irrespective of the origins of domestication, the horse genome is known to have been reshaped significantly within the last ∼2,300 years (Librado et al., 2017, Wallner et al., 2017, Wutke et al., 2018). However, when and in which context(s) such changes occurred remains largely unknown.

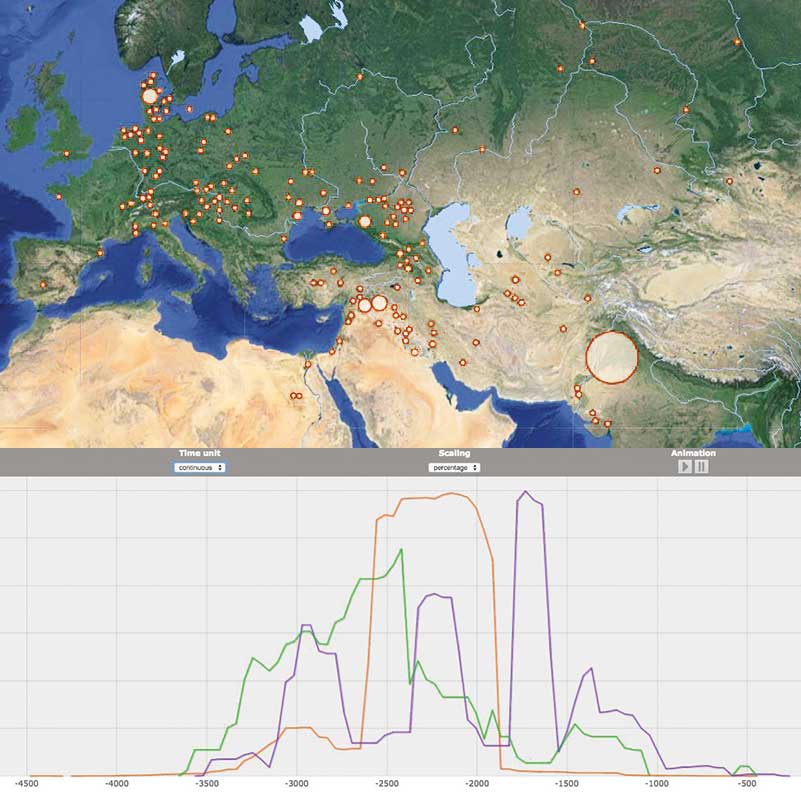

To clarify the origins of domestic horses and reveal their subsequent transformation by past equestrian civilizations, we generated DNA data from 278 equine subfossils with ages mostly spanning the last six millennia (n = 265, 95%) (Figures 1A and 1B; Table S1; STAR Methods). Endogenous DNA content was compatible with economical sequencing of 87 new horse genomes to an average depth-of-coverage of 1.0- to 9.3-fold (median = 3.3-fold; Table S2). This more than doubles the number of ancient horse genomes hitherto characterized. With a total of 129 ancient genomes, 30 modern genomes, and new genome-scale data from 132 ancient individuals (0.01- to 0.9-fold, median = 0.08-fold), our dataset represents the largest genome-scale time series published for a non-human organism (Tables S2, S3, and S4; STAR Methods).

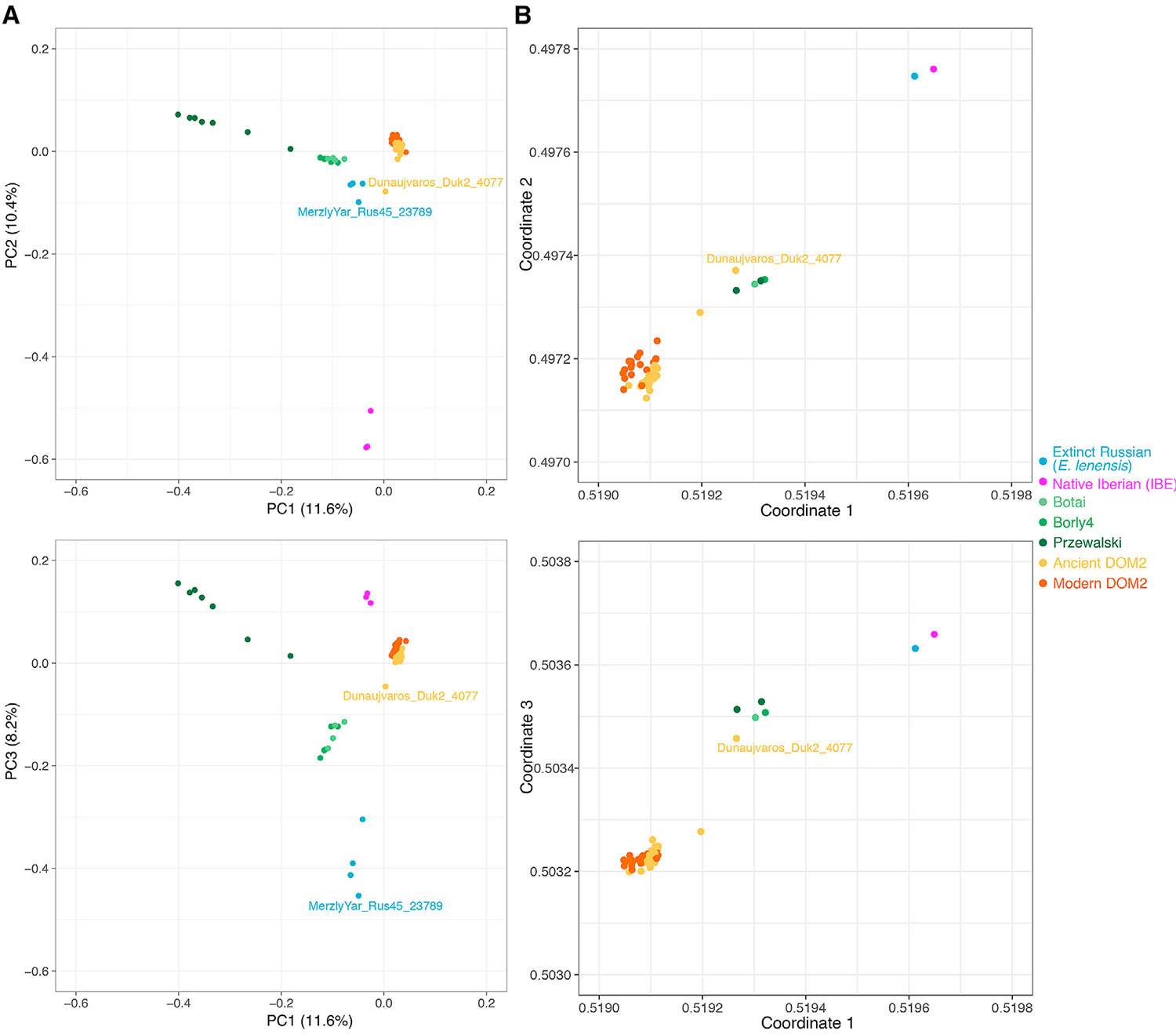

(A) Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of 159 ancient and modern horse genomes showing at least 1-fold average depth-of-coverage. The overall genetic structure is shown for the first three principal components, which summarize 11.6%, 10.4% and 8.2% of the total genetic variation, respectively. The two specimens MerzlyYar_Rus45_23789 and Dunaujvaros_Duk2_4077 discussed in the main text are highlighted. See also Figure S7 and Table S5 for further information.

(B) Visualization of the genetic affinities among individuals, as revealed by the struct-f4 algorithm and 878,475 f4 permutations. The f4 calculation was conditioned on nucleotide transversions present in all groups, with samples were grouped as in TreeMix analyses (Figure 3). In contrast to PCA, f4 permutations measure genetic drift along internal branches. They are thus more likely to reveal ancient population substructure.

Discovering Two Divergent and Extinct Lineages of Horses

Domestic and Przewalski’s horses are the only two extant horse lineages (Der Sarkissian et al., 2015). Another lineage was genetically identified from three bones dated to ∼43,000–5,000 years ago (Librado et al., 2015, Schubert et al., 2014a). It showed morphological affinities to an extinct horse species described as Equus lenensis (Boeskorov et al., 2018). We now find that this extinct lineage also extended to Southern Siberia, following the principal component analysis (PCA), phylogenetic, and f3-outgroup clustering of an ∼24,000-year-old specimen from the Tuva Republic within this group (Figures 3, 5A and S7A). This new specimen (MerzlyYar_Rus45_23789) carries an extremely divergent mtDNA only found in the New Siberian Islands some ∼33,200 years ago (Orlando et al., 2013) (Figure 6A; STAR Methods) and absent from the three bones previously sequenced. This suggests that a divergent ghost lineage of horses contributed to the genetic ancestry of MerzlyYar_Rus45_23789. However, both the timing and location of the genetic contact between E. lenensis and this ghost lineage remain unknown.

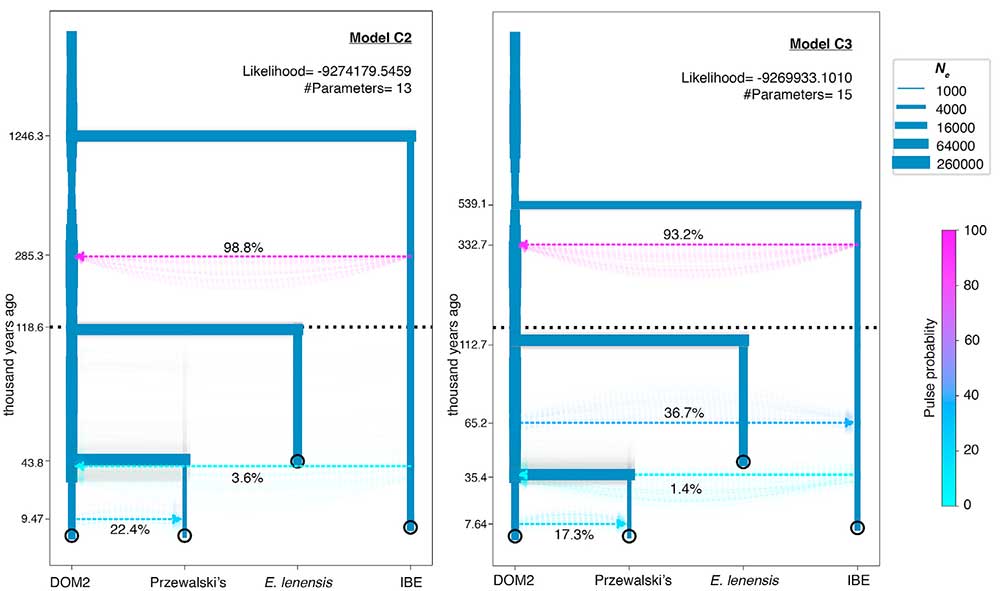

Modeling Demography and Admixture of Extinct and Extant Horse Lineages

Phylogenetic reconstructions without gene flow indicated that IBE differentiated prior to the divergence between DOM2 and Przewalski’s horses (Figure 3; STAR Methods). However, allowing for one migration edge in TreeMix suggested closer affinities with one single Hungarian DOM2 specimen from the 3rd mill. BCE (Dunaujvaros_Duk2_4077), with extensive genetic contribution (38.6%) from the branch ancestral to all horses (Figure S7B).This, and the extremely divergent IBE Y chromosome (Figure 6B), suggest that a divergent but yet unidentified ghost population could have contributed to the IBE genetic makeup.

Rejecting Iberian Contribution to Modern Domesticates

The genome sequences of four ∼4,800- to 3,900-year-old IBE specimens characterized here allowed us to clarify ongoing debates about the possible contribution of Iberia to horse domestication (Benecke, 2006, Uerpmann, 1990, Warmuth et al., 2011). Calculating the so-called fG ratio (Martin et al., 2015) provided a minimal boundary for the IBE contribution to DOM2 members (Cahill et al., 2013) (Figure 7A). The maximum of such estimate was found in the Hungarian Dunaujvaros_Duk2_4077 specimen (∼11.7%–12.2%), consistent with its TreeMix clustering with IBE when allowing for one migration edge (Figure S7B). This specimen was previously suggested to share ancestry with a yet-unidentified population (Gaunitz et al., 2018). Calculation of f4-statistics indicates that this population is not related to E. lenensis but to IBE (Figure 7B; STAR Methods). Therefore, IBE or horses closely related to IBE, contributed ancestry to animals found at an Early Bronze Age trade center in Hungary from the late 3rd mill. BCE. This could indicate that there was long-distance exchange of horses during the Bell Beaker phenomenon (Olalde et al., 2018). The fG minimal boundary for the IBE contribution into an Iron Age Spanish horse (ElsVilars_UE4618_2672) was still important (~9.6%–10.1%), suggesting that an IBE genetic influence persisted in Iberia until at least the 7th century BCE in a domestic context. However, fG estimates were more limited for almost all ancient and modern horses investigated (median = ~4.9%–5.4%; Figure 7A).

Iron Age horses

Y chromosome nucleotide diversity (π) decreased steadily in both continents during the last ∼2,000 years but dropped to present-day levels only after 850–1,350 CE (Figures 2B and S2E; STAR Methods). This is consistent with the dominance of an ∼1,000- to 700-year-old oriental haplogroup in most modern studs (Felkel et al., 2018, Wallner et al., 2017). Our data also indicate that the growing influence of specific stallion lines post-Renaissance (Wallner et al., 2017) was responsible for as much as a 3.8- to 10.0-fold drop in Y chromosome diversity.

We then calculated Y chromosome π estimates within past cultures represented by a minimum of three males to clarify the historical contexts that most impacted Y chromosome diversity. This confirmed the temporal trajectory observed above as Byzantine horses (287–861 CE) and horses from the Great Mongolian Empire (1,206–1,368 CE) showed limited yet larger-than-modern diversity. Bronze Age Deer Stone horses from Mongolia, medieval Aukštaičiai horses from Lithuania (C9th–C10th [ninth through the tenth centuries of the Common Era]), and Iron Age Pazyryk Scythian horses showed similar diversity levels (0.000256–0.000267) (Figure 2A). However, diversity was larger in La Tène, Roman, and Gallo-Roman horses, where Y-to-autosomal π ratios were close to 0.25. This contrasts to modern horses, where marked selection of specific patrilines drives Y-to-autosomal π ratios substantially below 0.25 (0.0193–0.0396) (Figure 2A). The close-to-0.25 Y-to-autosomal π ratios found in La Tène, Roman, and Gallo-Roman horses suggest breeding strategies involving an even reproductive success among stallions or equally biased reproductive success in both sexes (Wilson Sayres et al., 2014).

Lineage is used in this paper, as in many others in genetics, as defined by a specific ancestry. I keep that nomenclature below. It should not be confused with the “lineages” or “lines” referring to Y-chromosome (or mtDNA) haplogroups.

Supporting the “archaic” nature of the Hungarian BBC horses expanding from the Pontic-Caspian steppes are:

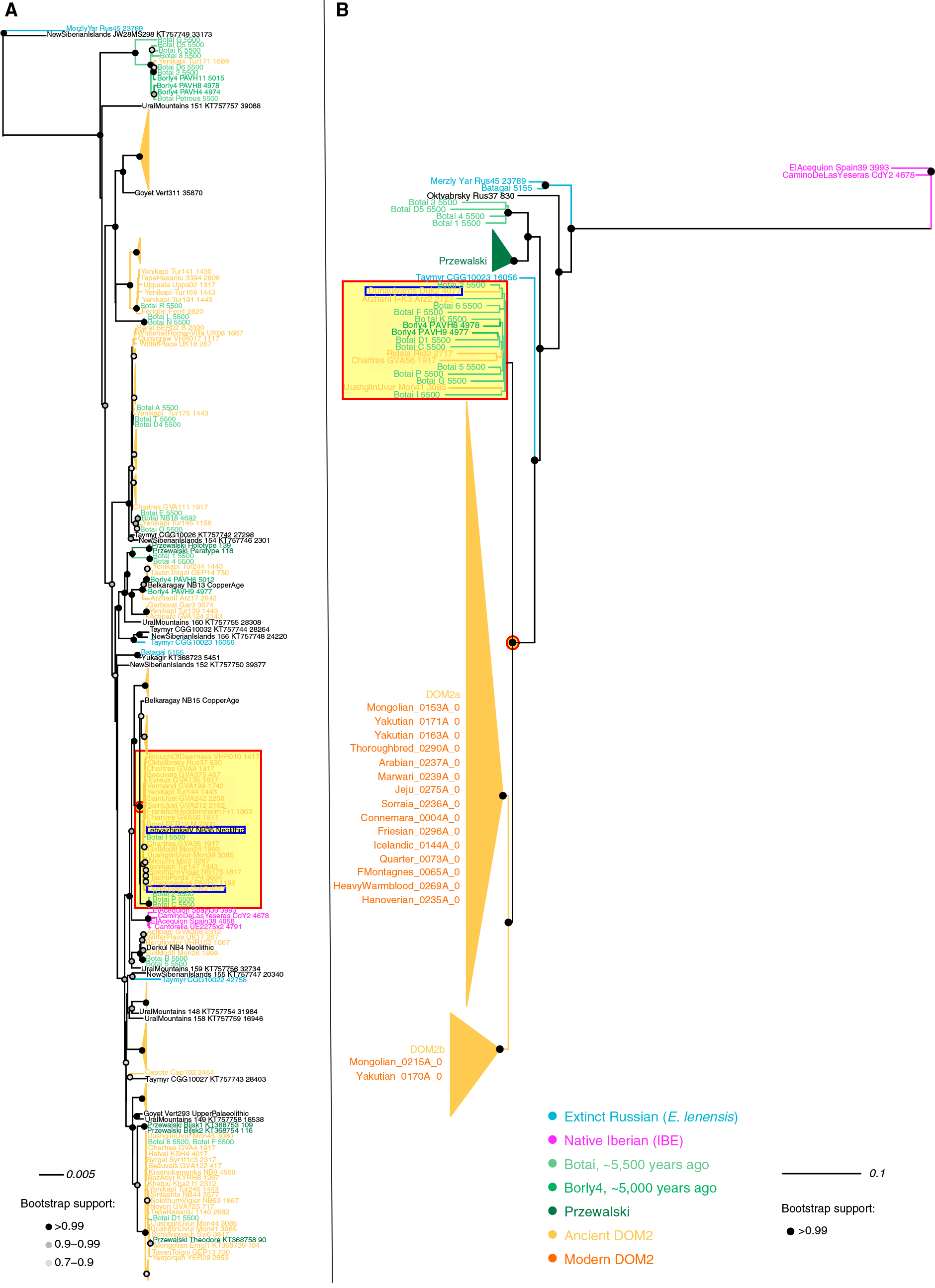

- Among Y-chromosome lines, the common group formed by Botai-Borly4 (closely related to DOM2), Scythian horses from Aldy Bel (Arzhani), Iron Age horses from Estonia (Ridala), horses from the Xiongnu culture (Uushgiin Uvur), and Roman horses from Autricum (Chartres).

- Among mtDNA lines, the common group formed by Botai samples, LebyazhinkaIV NB35, and different Eurasian domesticates, including many ancient Western European ones, which reveals a likely expansion of certain subclades east and west with the Repin culture.

- the lineage of the Dunaujvarus Duk2 4077 sample and the North-West Indo-European expansion (ca. 3000-2500 BC).

- the lineage of the Halvai KSH4 4017 and Sintashta NB46 4023 samples and the later Proto-Indo-Iranian expansion (ca. 2500-2000 BC).

- Yamna expansion to the west “with horses and wagons”, with a more homogeneous ancestry in modern Europeans due to later migrations from the east (and north):

- “Descendants” of Yamna (once the culture was already “dead”), expanding to the east mainly with Corded Ware ancestry:

- The genetic and cultural barrier of the Pontic-Caspian steppe – forest-steppe ecotone

- Mitogenomes suggest rapid expansion of domesticated horse before 3500 BC

- Origin of horse domestication likely on the North Caspian steppes

- Ancient DNA upends the horse family tree

- Domesticated horse population structure, selection, and mtDNA geographic patterns

- About Scepters, Horses, and War: on Khvalynsk migrants in the Caucasus and the Danube

- Steppe and Caucasus Eneolithic: the new keystones of the EHG-CHG-ANE ancestry in steppe groups

- Domestication spread probably via the North Pontic steppe to Khvalynsk… but not horse riding

- Differing modes of animal exploitation in North Pontic Eneolithic and Bronze Age Societies

(…) DOM2 contributed 22% to the ancestor of Przewalski’s horses ca. 9.47 kya, suggesting the Holocene optimum, rather than the Eneolithic Botai culture (∼5.5 kya), as a period of population contact. This pre-Botai introgression could explain the Y chromosome topology, where Botai horses were reported to carry two different segregating haplogroups: one occupied a basal position in the phylogeny while the other was closely related to DOM2. Multiple admixture pulses, however, are known to have occurred along the divergence of DOM2 and the Botai-Borly4 lineage, including 2.3% post-Borly4 contribution to DOM2, and a more recent 6.8% DOM2 intogression into Przewalski’s horses (Gaunitz et al., 2018). Model C2 parameters accommodate all these as a single admixture pulse, likely averaging the contributions of all these multiple events.

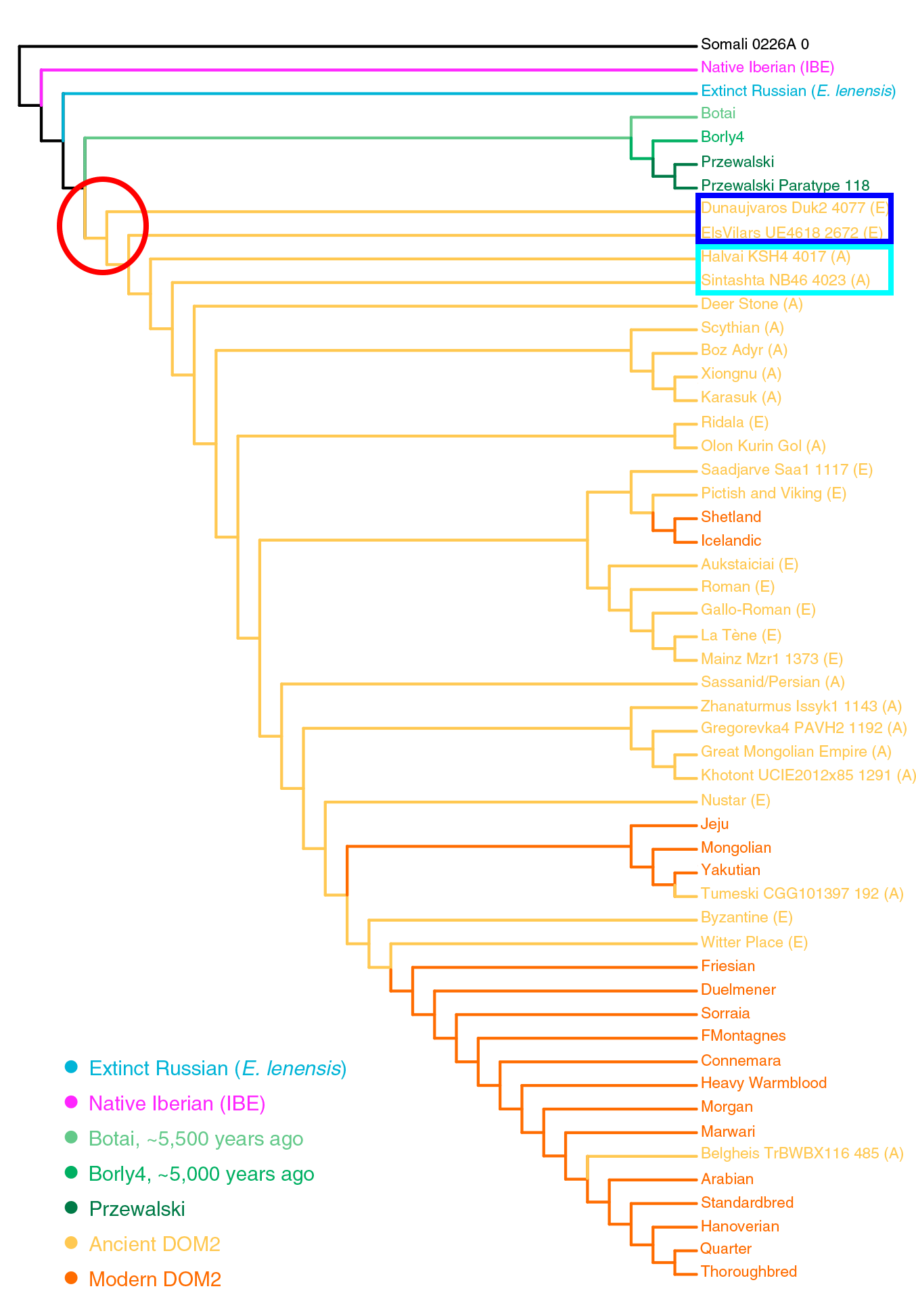

(A) Best maximum likelihood tree retracing the phylogenetic relationships between 270 mitochondrial genomes.

B) Best Y chromosome maximum likelihood tree (GTRGAMMA substitution model) excluding outgroup. Node supports are indicated as fractions of 100 bootstrap pseudoreplicates. Bootstrap supports inferior to 90% are not shown. The root was placed on the tree midpoint. See also Table S5 for dataset information.

Image modified from the paper, including a red square in archaic groups that contain the Hungarian sample, and a red circle around the most likely common ancestral stallion and mare from the Pontic-Caspian steppes.

The paper cannot offer a detailed picture of ancient horse domestication, but it is yet another step in showing how Repin/Yamna is the most likely source of expansion of horse domesticates in Eurasia. Even more interestingly, Yamna settlers in Hungary probably expanded an ancient lineage of that horse at the same time as they spread with the Classical Bell Beaker culture. Remarkable parallels are thus found between:

The expansion of an ancient line of horse domesticates related to Yamna Hungary/East Bell Beakers seems to be confirmed by the pre-Iberian sample from Vilars I, Els Vilars4618 2672 (ca. 700-550 BC), likely of Iberian Beaker descent, showing a lineage older than the Indo-Iranian ones, which later replaced most European lines.

NOTE. For known contacts between Yamna and Proto-Beakers just before the expansion of East Bell Beakers, see a recent post on Vanguard Yamna groups.

The findings of the paper confirm the expansion of the horse firstly (and mainly) through the steppe biome, mimicking the expansion of Proto-Indo-Europeans first, and then replaced gradually (or not so gradually) by lines brought to Europe during westward expansions of Bronze Age, Iron Age, and later specialized horse-riding steppe cultures. The expansion also correlates well with the known spread of animal traction and pastoralism before 2000 BC:

EDIT (3 MAY 2019): A recent reminder of these parallel developments by David Reich in Insights into language expansions from ancient DNA:

DR: inference is that two major migrations: farmers from Anatolia, followed by steppe pastoralists. Who are they? They took horses and wagons and spread. See rapid 90% pop turn over in Britain. Similar timing in Iberia, but a bit less turnover, and more period of overlap

— Joshua G. Schraiber? (@jgschraiber) May 2, 2019

DR: spread of steppe ancestry to the east likely a result of spread of yamnaya descendents, since yamnaya were dead. High genetic similarity to corded ware people.

— Joshua G. Schraiber? (@jgschraiber) May 2, 2019

Another recent open access paper on horse domestication is The horse Y chromosome as an informative marker for tracing sire lines, by Felkel et al. Scientific Reports (2019).